Dove

On Kazuo Ohno, medieval mystical choreography and The Song of Songs: Performance notes for 'Dove' performance - St. James Avebury, 21st June'25.

Over the Summer Solstice weekend 2025, St. James’ Church in Avebury celebrated 10 years of housing the Hiroshima Peace Flame.

The perpetual flame was originally lit by the Grandmother of Yamamoto Tatsuo, who’d collected some of the embers still burning from the Hiroshima bomb and brought them home to Hoshino. His grandmother kindled a flame from the embers and tended the flame for 12 years, taking central place on the Buddhist family altar. They had lost a relative in the bombing.

The fire was a flame of love in memorial of those who had lost their lives.

In 1968, the Fire of Peace became a monument in Hoshino where you can still visit it today. From that original flame, candles were lit. One was taken on pilgrimage across the US and 10 years ago it was brought to St James’ Church in Avebury, England - an ancient sacred site, where people flock to celebrate the light of the Solstice year after year.

To commemorate the flame, St. James had a weekend of artists come and perform, marking 80 years since the bomb. We were praying for peace.

I gave a half hour performance titled ‘Dove’ drawn from The Song of Songs.

Here are my performance notes, initially this was going to be spoken - but plans changed, so it’s written with a somewhat oral voice.

If you’re reading this and came along - thank you.

‘So I train in the contemporary Japanese performance art: Butoh dance.

Butoh means something like dance-step in Japanese and is a metamorphic dance form that celebrates borderlessness, imperfection and relationality; amongst many other things. But its central focus, as an art form emergent from the devastations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one could describe as "beauty from ashes".

There were two main founders of Butoh, Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata. Two men really on opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of personality. I'm going to talk mostly about Kazuo Ohno, as the lineage of teachers I follow are predominantly students of his, and in the spirit of the commemoration of the flame this weekend I want to talk about his spirit and approach to dance as prayer; dance as a fathoming of the unfathomable — be that the reality of Hiroshima or the reality of Christ — he entered intimately into those mysteries through dance.

Born October 27th 1906 in Hakodata, Hokkaido — a modern town for the time in Northern Japan. His mother had a huge impact on his life and teaching; reading him ghost stories as a child and occasionally taking him and his siblings to the local church to pray — in the absence of a Buddhist temple in the local area. She herself was not a Christian but an Amida-Buddhist and he was raised with Buddhist values thanks to her for whom God is God, prayer is prayer.

If you go to Japan, anyone who's visited the shrines will know that often on the plaques, side by side you'll find the same shrine dedicated to the Buddhist deity as well as the Shinto deity — the indigenous faith of Japan. This isn't entirely without controversy, but it's worth mentioning that the notion of plurality is not something of a major controversy in Japan. Multiplicity, sometimes even paradoxical simultaneity isn't a wholly alien concept to the Japanese way of thinking — in their language, for example a sign or the word itself is a unity that holds within it a multitude of meanings. Like an ocean with many fish.

Kazuo lost a sister tragically when young due to an unfortunate incident with a train. I would guess this was his first experience of unspeakable grief.

The kind of grief that shouldn't really be happening.

In 1926 he moved to Tokyo at the age of 20, trained as a school gymnastics teacher before being sent into military service for 14 months. Upon return he took up a teaching post at a school in Yokohama and at 24 he was baptised into the Christian faith, bringing his Buddhist values with him.

For the rest of his life, the Christian story was at the heart of his world and his art.

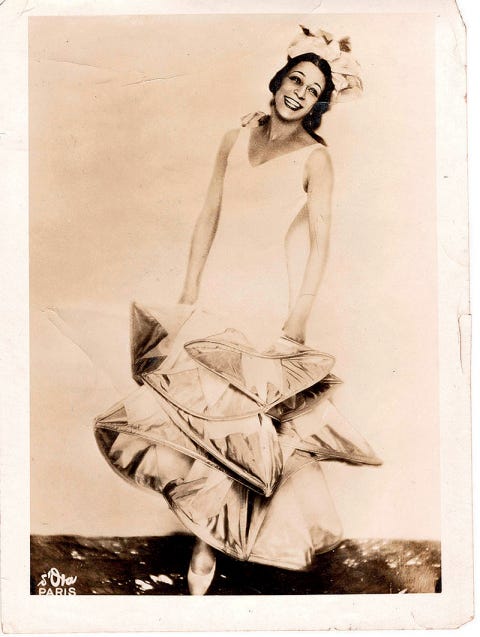

One day Kazuo went to see a performance by the legendary La Argentina — otherwise known as "Queen of the Castanets". This was a woman of fire. Born in Buenos Aires in 1890, this woman roared around the world as the "Flamenco Pavlova".

If anyone could dance, it was her.

When Kazuo Ohno first saw her he said:

"Her magic hit me like a lightening bolt.

I can never forget this encounter."

And from that moment on, he yearned in his most secret heart, to become a dancer. Eventually, after he married, it happened.

In 1933 he began training as a dancer in preparation for a new role at a Baptist Girls' School where the gymnastics teacher was required also to teach dance. On his training, with renowned contemporary dancers of the time, he became interested in form and expression — the relationship between inside and outside.

The untimely death of La Argentina in 1936 hit him hard. Ohno was a man frequently twisted by grief and dance became how he understood life.

In 1938 his son, later his dance partner and respected artist in his own right, Yoshito was born. In that same year of 1938, Kazuo was called to military service.

No one knew then just what was on the horizon.

Kazuo didn't return home until 1946, the last two years of his service was spent as a prisoner of war. He returned to his teaching position at the Baptist Girls' School where he stayed teaching until the 1980's.

Needless to say, Japan wasn't the same as when he'd left in 1938 — and neither was his dance. He began to reject the western concepts that had trickled into the Japanese modern dance world he'd been immersed in previously to work on something of his own. Finding his own flower blooming through the rubble, the dance for him both a dove hiding in the cliffs and the voice that calls them out.

Over time he completely turned the popular contemporary choreographic methodology of the times upside down to develop an immersive, provocative and emotional dance form where one empties to fill themselves with internal imagery, bringing the world inside oneself to understand it more and be moved by the heart that is participative in understanding.

This is loving to know, and knowing to love.

The Japan he returned to, post WWII was experiencing a severe identity crisis. Plagued with American / Western promises of progress which only served to further dismantle traditional communal values.

Butoh emerged from the pressure — the seemingly impenetrable rock face of the western occupation in the unfathomable aftermath of "the special bomb" as some Japanese media of the time named it. Hijikata once described Butoh as a disinterring of “the body that has not been robbed”.

Butoh set itself up as an artform that would tend the garden of the human body and the ecological body after such a shock. A cultivation of bodily truth and the essential sensual realities of being and becoming to counteract the anaesthesia of American influence.

I'm not talking traditional American values here, I'm talking: McDonalds, electric lighting, pornography - trains. These things that seem so normal for some were revealed as violent forces at the time in Japan and for people like Ohno and Hijikata it was just clear as day.

Ohno never outwardly talking about his time in the military and as a prisoner of war, instead, he said in his workshops "when I dance, I carry all the dead with me."

I can't really imagine many things more Christ-like than that.

"The soul becomes ashes..." he says,

"My soul spreads out across the vast sky, then becomes ashes and falls."

It was his mother's death in 1962 that radically changed his approach to dancing once more. Her last words were remarkable, she said:

"A flatfish swims in my body."

A flatfish, for anyone who doesn't know, rests under the sands of the ocean bed and suddenly springs in life. This image for Ohno became a revelation of the embodiment of genesis. In the beginning. A leap in the cosmic womb: The continual wellspring of now — and over the years a complete cosmology emerged.

By the 70's in his vision, the womb was a microcosm of the entirety of creation. The dance became a womb-space necessary to the continual renewal of life. Now, in dancing, he's participating in an act of creation; a partnering with divinity.

If you read his workshop words and have some literacy in Marianic theology it makes for profound reading. Especially in consideration of Mary as the spouse of God.

Kazuo's work became more explicitly about annunciation and incarnation of word from word, image from image, metamorphosing and intermixing together, as if making love, springing up inside him.

A dancer as a fountain in a garden.

He says,

"We as human beings are erotic in nature and life, since the erotic is close to the origins of life. Eventually we are born and separate from the other, but our original bond with her contains the erotic union of the mother and the father."

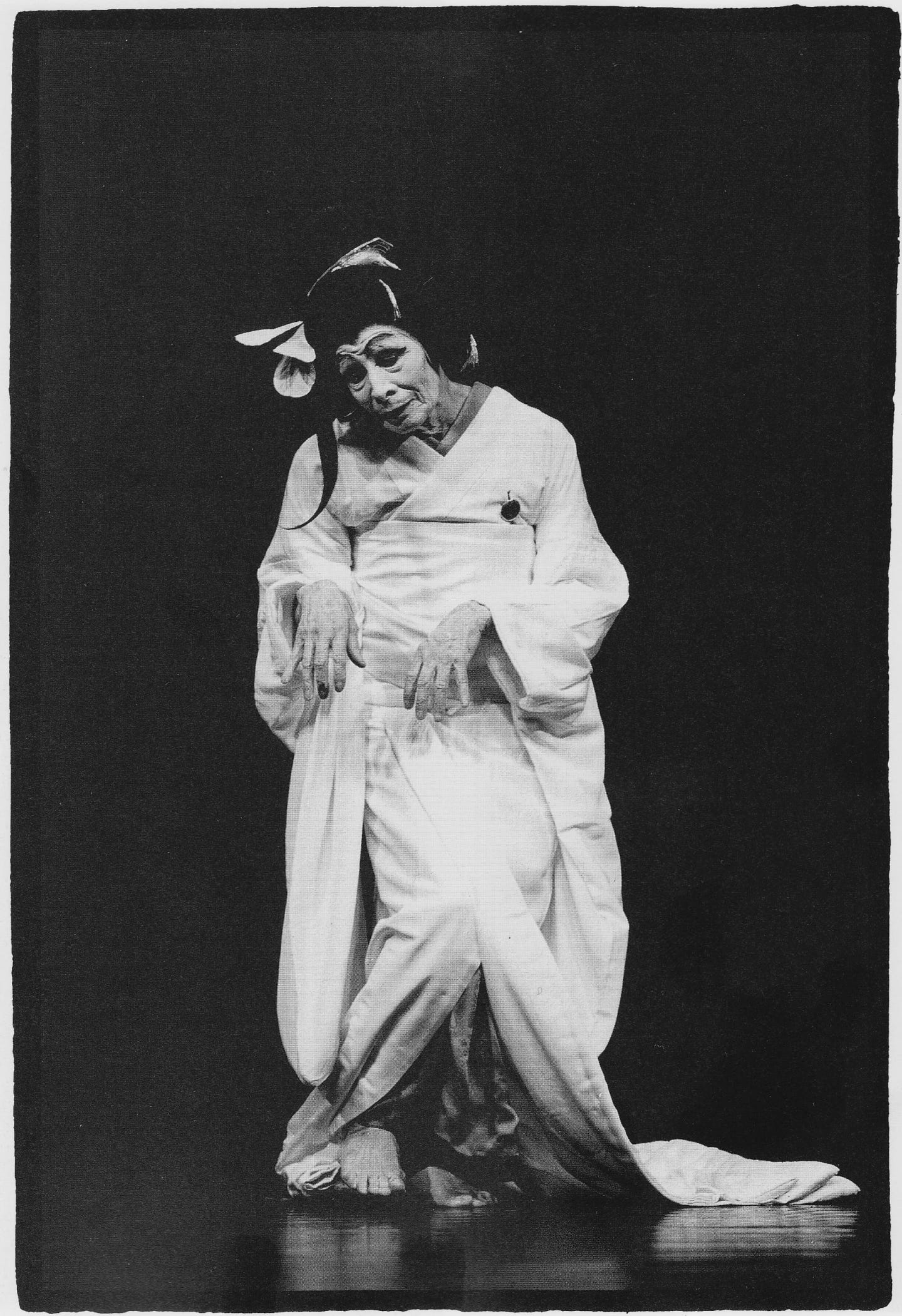

This is a brief portrait of a man who knew grief, who knew suffering, unspeakable violence, helplessness and hope. His faith in Christ and his love of creation, particularly his love of people, was unceasing and he spoke about it through his dance right up until he died aged 103 in 2010.

I wanted to give a lot of time to him here because he's a rich vein in the body of this work and it felt like it would be an injustice of some kind not to give weight in memorial of this man who devoted his life to dancing creation out of destruction, flowering ghosts and the total embryonic innocence of the erotic pulse of life.

Another influence of this work is the medieval phenomenon of mystical dance.

I'm jumping to another world now but one I hope you'll catch the thread I'm on here.

Dance in Europe in the middle ages was mostly communal. At the time, dance was a winged life of communities in Christian Europe. One of the things that stayed for a long time in post-Christian Britain were the traditional pagan folk dances. It wasn't until witch hunts and the reformation that it became a suspicious activity. Before this it was seen as an essential practice in the refining of the solidarity of the Christian social body.

At the height of all this in the late middle ages, there emerged these individual women mystics who intimately united with Christ through dance. It was supported by men of monastic communities and recognised as deeply mysterious.

At a time when feminine spirituality was flourishing, this mystical dance emerged.

I love it because, like Butoh, it challenges assumptions about dance many of us still carry today. Like Butoh, mystical dance is about frailty and honesty, strength and prayer, an embrace of the paradoxical — these individual women were springing up like lilies across the fields of European Christianity.

And for these practitioners — I'm quoting Katharine Dickason here, the authority on this subject — “mystical dance was both imagined and physical, private and performed, ineffable and transferable." She says, “mystics reimagined the graphic texture of dance through nuptial imagery, erotic encounter and contortionist spectacles” [Book: Ringleaders of Redemption]

Ohno would have ached to have become one of these women. He would often dance in women's clothes, once performing as La Argentina in 1953, following the tradition of the Noh theatre, where the pinnacle performance of the male actor's career was mastering the dance of the Celestial Maiden.

He was a fan of Blake and Rilke and Hemingway — He threw all of himself into becoming the old man on the sea — I imagine he would have poured himself over the writings of Mechtild of Magdeburg or Adelheit von Hiltegarthausen or of the time “when Sister Heilrade found herself overcome by celestial harmony, her soul, as it were, began to dance in her body”.

I don't have time to go further into this here today, but I have a feeling that Ohno would have related to Mechtild when she writes:

"The soul is formed in the body with human qualities but has a divine shimmer about it and shines through the body as radiant gold shines through pure crystal... just think what such movement is like."

Being a lantern for God is something that I, as a Christian, am particularly interested in - that Kenosis; the emptying of self to allow for theosis: the illumination of God peering through the lattice of our bodies and all of creation.

The Song of Songs, an erotic love poem at the heart of the Bible is the ultimate source I'm drawing from here — The Title "Dove" refers to the dove hiding in the cleft of the rock, an image in the poem. The story follows a woman, the bride, at first she is exiled, exhausted and thoroughly burnt by the excruciating heat of the noonday sun.

We follow her as she follows her Bridegroom, who can only see her beauty through the ashes. He says:

"O my dove, that art in the cleft of the rock,

in the secret places of the cliff,

let me see thy countenance;

let me hear thy voice.

For sweet is thy voice and thy countenance lovely."

His encouragement of her and the quality of his gaze are what transforms her into a fruiting, blooming garden.

"I am the rose of Sharon," she says,

"and the lily of the valley."

Rejoicing in the Bridegroom, likening him to an apple tree, she continues:

"I delight to sit under his shade and his fruit is sweet to my taste.

He brought me to the house of wine, and his glance before me is Love."

And he, in his own words, is ravished by her beauty. Barely able to look at her.

That beauty involves her flaws — a truly Butoh approach to vision.

"I am come into my garden, my sister, my bride,

I have plucked my myrrh with my spice,

I have eaten my honeycomb with my honey;

I have drunk my wine with my milk;

Eat, o friends, drink! And be drunk with love!"

Later exclaiming to her:

"This thy statute is like to a palm tree,

thy breasts to clusters of grapes:

I said — I will ascend the palm tree!

I will take hold of the boughs thereof!

and may thy breasts be as clusters of the vine

and the scent of the nose like apples

and the roof of thy mouth like the best wine for my beloved,

that goeth down sweetly, coursing to my beloved as smooth wine,

causing the lips of those who sleep to speak."

So, although I've only directly spoken of the dove briefly here, I hope perhaps you've found at least one instance of her nesting in secret places of this speech and the dance that just happened.

I want to close this now with a reading from Isaiah 61 in the spirit of the prayer we're holding this weekend in commemoration of the Hiroshima flame here at the church. If the flame had a human voice, this might be what they'd say:

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted

to proclaim freedom for the captives

and release from the darkness for the prisoners

to proclaim the year of the Lord's favour and the day of vengeance of our God,

to comfort all who mourn,

and provide for those who grieve in Zion

To bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes

the oil of joy instead of mourning

and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair.

They will be called oaks of righteousness,

a planting of the Lord for the display of his splendour.

Thanks to Kazuo Ohno — who I think we could truly call an oak; the flame and the Yamamoto family who lit it, all that time ago in such a fragile and courageous moment; all who've held it and hold it; Sarah Perceval who made the wreath; thanks to Fr. Jonathan for inviting this to happen today here at St. James and thanks to all of you for bearing with me!’